ARE WE IN HOT WATER?

Warming ocean temperatures are impacting Nantucket waters.

story by Greta Feeney

This year, the late summer heat on Nantucket extended well into autumn. With ocean temperatures expected to hover around 60 degrees Fahrenheit through mid-November, the waters will be chilly but not mind-numbing, allowing some swimmers to expand their season to nearly eight months out of the year.

But the allure of a seemingly endless Nantucket summer is quickly offset by the stark realities of climate change, and concerns over accelerated warming of the North Atlantic Ocean—which on any given day is around 6 degrees warmer than the historic average—are rippling through the community.

New England’s waters are warming and not just by a little. In 2021, the Gulf of Maine Research Institute announced that the temperature of inlet waters adjacent to Maine and northern Massachusetts was the highest on record, with faster rates of warming than 96 percent of the world’s oceans and annual rate increases of 0.1 degree Celsius (0.18 degree Fahrenheit) over the past four decades.

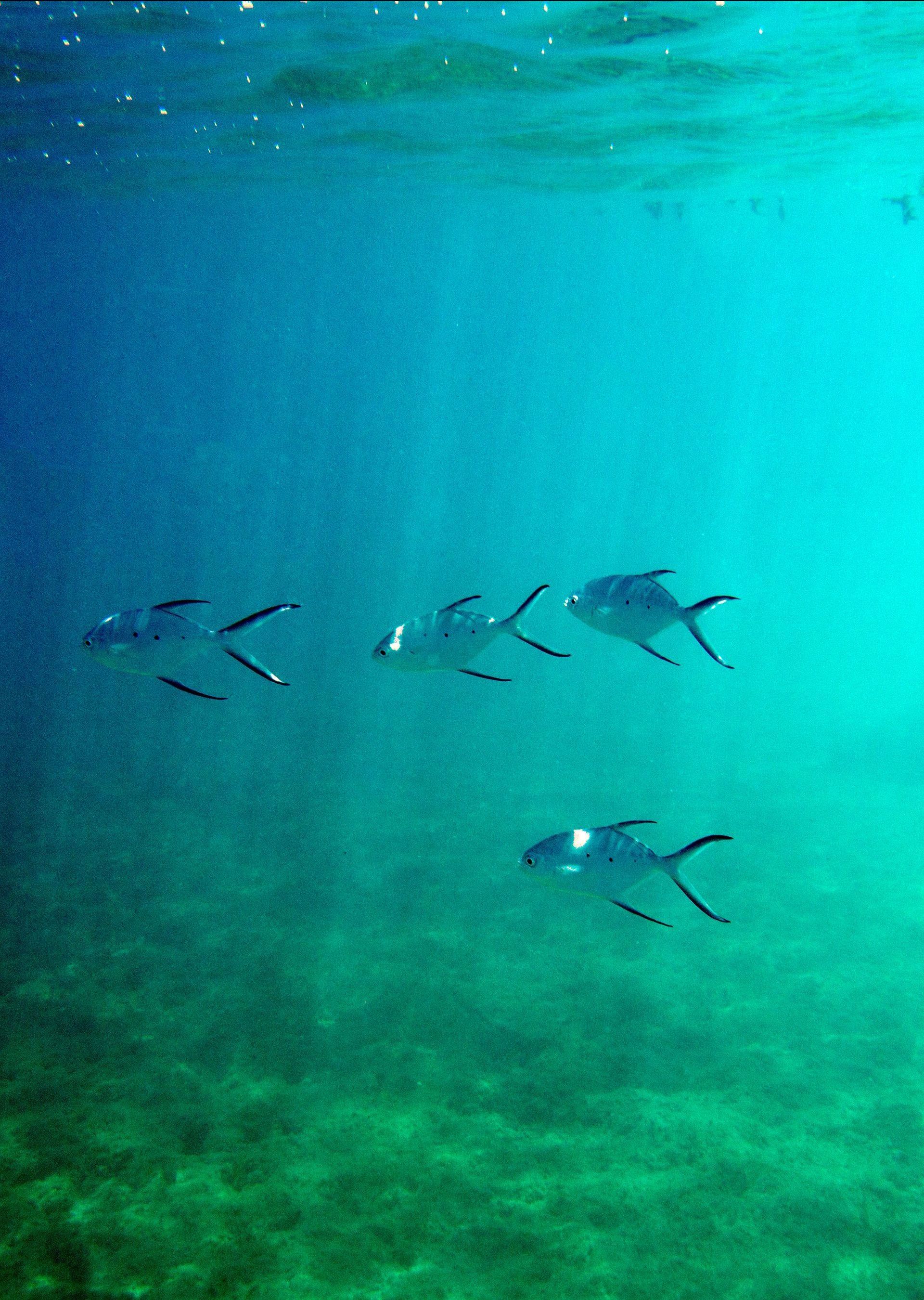

This is seemingly a pattern for the rest of the world, as well. From June through September, an estimated 40 percent of the world’s oceans experienced marine heatwaves, resulting in the mass death of Amazonian pink dolphins in Brazil, widespread coral bleaching in the Florida Keys and anomalous tropical fish sightings throughout New England due to an increase in what scientists call “warm core rings”—swirling blobs of the swollen Gulf Stream that break off from the main current and carry unwitting warm-water sea creatures north into cooler climes.

The Maria Mitchell Association has been monitoring marine biodiversity and tropical fish abundance in Nantucket’s eelgrass ecosystems for over 15 years. According to the association’s aquarium director, Jack Dubinsky, sightings of warm-water species are becoming more frequent. “Over the last decade, the MMA has found an average of three to six tropical fishes in Nantucket every season. In 2023, we found and identified 58 tropical fishes, including a single tow of the seine net [in early October] that had 25 juvenile permit (Trachinotus falcatus) and six juvenile mojarra (Eucinostomus sp.). We suspect the extraordinary tropical fish abundance is most likely due to higher survival rates of tropical fish larvae facilitated by record-breaking Atlantic Ocean temperatures this year.”

Ocean temperatures are influenced by myriad complex factors including deep sea currents, volcanic eruptions and recurring patterns such as El Niño and La Niña, but scientists correlate recent accelerated warming with exposure to increased concentrations of greenhouse gases— excess carbon dioxide and heat trapped in the atmosphere are transferred upon contact to the cooler ocean water, leading to warmer temperatures and increased acidification. This dynamic climatic relationship between sea and sky is, in part, how the oceans function collectively as the world’s largest “carbon sink.”

This was exemplified in late July, when nine Nantucket beaches were closed to swimmers due to high bacteria counts. One month later, for the second year in a row, downtown beaches were closed after being found sullied by a sulfuric-smelling anoxic sludge.

Scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution described an uptick in hypoxic conditions at the southern end of Cape Cod Bay near Barnstable and in the waters between Provincetown and Wellfleet. These low-oxygen “dead zones,” according to the institution, are the result of imbalances in algal growth spurred by excess nutrient loads and increased upper ocean stratification, in which the warmer layer of seawater expands quickly relative to the cooler one, resulting in changes in water density—a complex mixing process also affected by shifting northeasterly wind patterns.

Days after the decomposing algae shuttered beaches, a trio of distressed and disoriented dolphins stranded themselves in the Creeks and on Coatue, only to circle back again after volunteers from the Marine Mammal Alliance tried to release them into deeper, cooler waters. The mid-August stranding event foreshadowed the September release of the 2023 State of the Ecosystem report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The report presented a sobering look at climate resiliency in the Northeast shelf ecosystem and its fisheries that underscores the increasing vulnerability of marine mammals to climate change.

NOAA researchers found that more than 70 percent of the 100 species of marine mammals studied are vulnerable to threats such as loss of habitat and food due to increased water temperatures, low levels of dissolved oxygen in sea water and other changes in ocean chemistry that can affect sound transmission underwater—an impact that disrupts the sonar-like echolocation whales and dolphins use to communicate and hunt.

On factors specific to Nantucket, that could theoretically result in marine mammal strandings like those seen in August. The Maria Mitchell Association’s Dubinsky explains. “I think the shallow environment, along with the effects cited in the NOAA study could possibly explain some of the stranding, but I imagine it would be difficult to ascertain whether the cause of the specific recent stranding event was due to anthropogenic changes to the marine environment or if it was a ‘natural’ occurrence. Long-term monitoring of strandings events and analysis of stranding trends will help us better understand how climate change affects marine mammal strandings on Nantucket.”

The Marine Mammal Alliance Nantucket team with one of the dolphins that was stranded on Nantucket in August. Photos by Kit Noble

Because the confluence of issues that contribute to a rapidly warming North Atlantic Ocean are largely out of their control, most local scientists are opting to hunker down on the more immediate problems affecting the health of Nantucket Harbor, while protecting the island’s coastal wetlands and ponds. RJ Turcotte, waterkeeper at the Nantucket Land & Water Council, has been using remote sensors to track increased ocean temperatures at eelgrass restoration sites at Monomoy and Fifth Bend since 2018.

“The temperatures in the harbors have been regularly stressing our eelgrass meadows,” Turcotte says. “Once the water temperature gets over about 75 degrees Fahrenheit, these plants stop growing—they are simply trying to survive. By July, our shallow harbors are regularly reaching this threshold temperature and staying there until fall. This shortens the growing season, especially in the northern reaches of Nantucket Harbor, which aren’t as well-flushed with cooler ocean water by the tides each day. We are concerned that these rising temperatures will cause us to lose these critical eelgrass meadows, which are the foundation of the Nantucket Harbor habitats.”

The Nantucket Conservation Foundation monitors the ocean temperature as a variable in many of its research projects around the island, including a long-term project tracking mating populations of horseshoe crabs at Warren’s Landing in Madaket Harbor and a Polpis Harbor oyster reef restoration project. Since 2010, the foundation’s researchers have observed correlations between an accelerated increase in water temperatures and horseshoe crab mating season happening earlier in the spring.

As the harbor continues to warm, Nantucket’s coastal wetlands will play an increasingly important role in countering the impacts of nutrient loading and the threats caused by increased acidification. Dr. Jennifer Karberg, NCF director of research and partnerships, explains how Nantucket’s 1,600 acres of salt marsh—1,200 of which are managed by NCF—“act as filters, reducing nutrient loading and filtering water as it reaches the harbor.” Regarding ocean acidification, Nantucket’s coastal wetlands “store significant amounts of carbon in their soils.” Part of NCF’s mission is studying and managing local salt marshes to increase carbon storage, which helps improve harbor health.

Ecologist Dr. Sarah Bois, director of research and education at the Linda Loring Nature Foundation, points out that, when it comes to warming oceans, “fisheries data is a focal point for the scientific community because it is of economic interest to everyone. The climate change aspect is more when the populations change. With fish, they can move north, or they can move deeper. Habitat fluctuations occur according to what the tolerances are. The black sea bass is one that gets talked about a lot. It was seen sporadically here and there, but as waters warmed, the populations have moved north. Now, they are a pretty constant fishery.”

Although he acknowledges the seriousness of concerns about climate change, second-generation charter boat captain Bob DaCosta doesn’t feel alarmed by increased sea water temperatures. “This year, temperature-wise it was maybe a degree or two warmer,” he says. “The water gets warmer earlier and stays warmer longer. We haven’t had any fall weather. The bait pattern has changed, though. We are seeing a difference in bait patterns year after year, and the bait pattern this year was completely off. We had to go south more to catch tuna because that’s where the bait was. You just have to adapt.”

We all have to adapt, but how? Nantucket’s experts emphasize the need to reduce nutrient pollution such as fertilizer runoff in light of increased ocean temperatures and acidification. Stormwater runoff infrastructure must also be improved to keep pollutants out of the harbor, and initiatives like the Nantucket Land & Water Council’s new eelgrass-friendly moorings must be supported and implemented so that boaters can help preserve the harbor while still enjoying it each summer. The Maria Mitchell Association has recently launched an ocean acidification monitoring project that will deploy oceanographic buoys in Nantucket Harbor to monitor seawater conditions. It is seeking support for this important, partially funded initiative, which will allow for independent assessments of several oceanographic parameters, including acidity, temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen and nitrate, the primary nutrient responsible for algal blooms in marine systems.

The ocean connects us all. It has also been a buffer against the full consequences of human-caused climate change, but the excess heat and carbon absorbed by the ocean are changing our marine ecosystems more quickly than predicted. Ocean innovation solutions are also accelerating, but systemic change will require strong leadership, technological innovation and public-private collaborations. Now, more than ever, the Nantucket community needs to lead the way as pioneers in the new blue economy.

“One of the things that gives me hope is human ingenuity,” says Dr. Kathy Mills, who heads the U.N. Ocean Decade’s fisheries strategies unit and is a senior research scientist at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute. “I think that spirit is an innate part of human culture.”