AMERICAN HERO

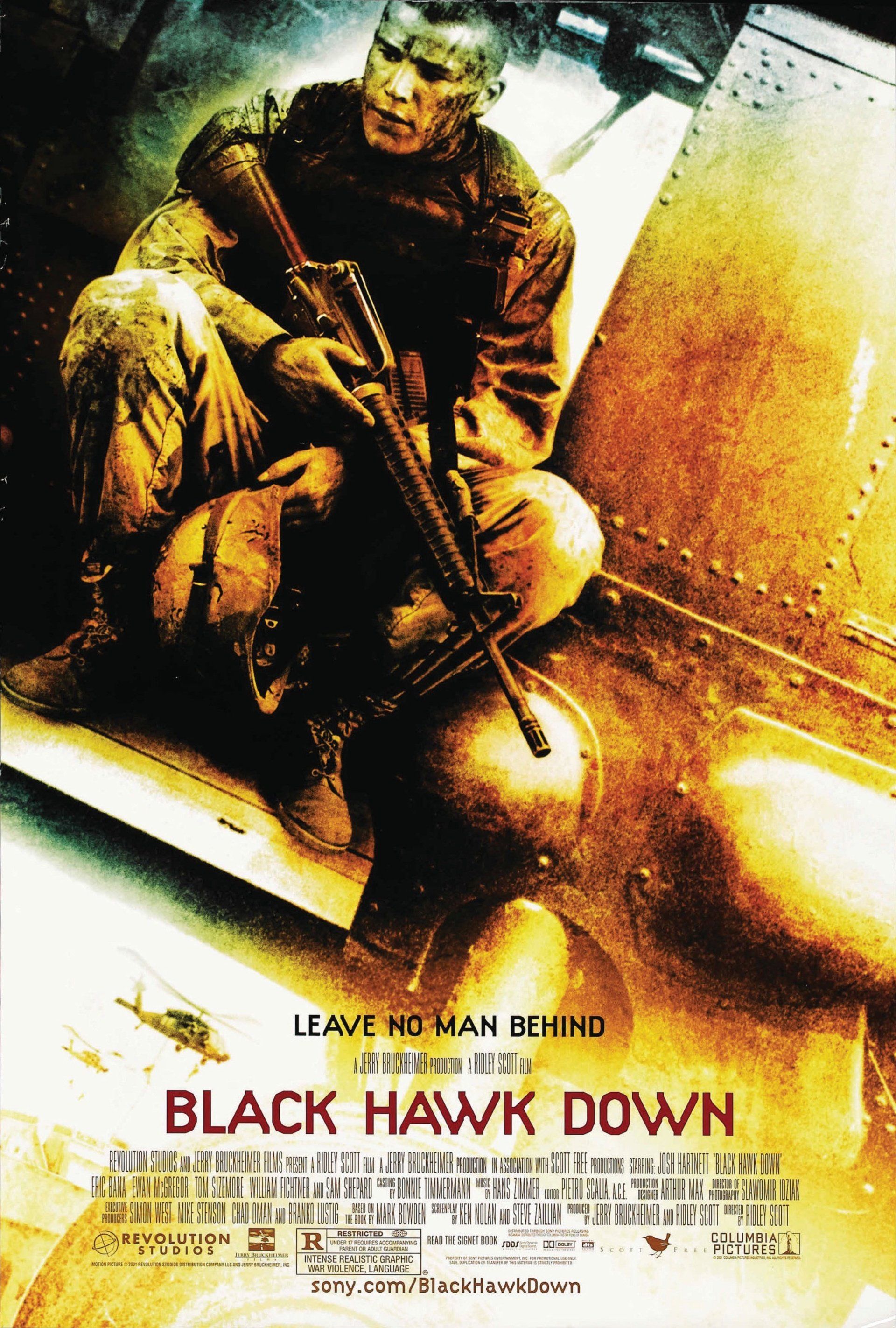

Lessons from the real Army Ranger who inspired Black Hawk Down.

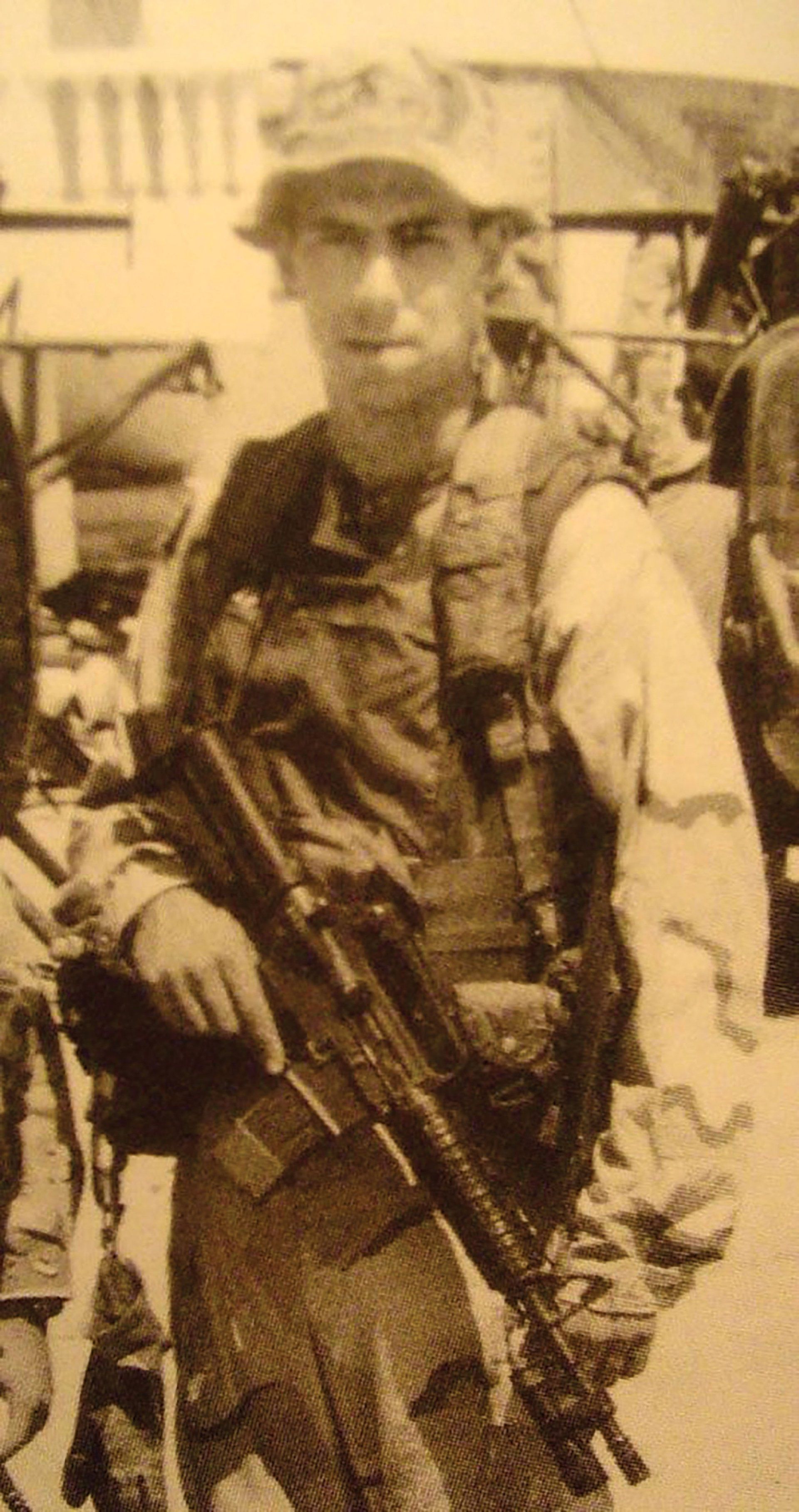

Retired First Sergeant Matt Eversmann was a soldier’s soldier. On October 3, 1993, Eversmann was placed in charge of a group of Army Rangers to lead a daytime raid to capture warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid in Mogadishu, Somalia. Eversmann and his men found themselves outgunned and outmanned in a deadly raid that was depicted in the epic film Black Hawk Down. Portrayed by actor Josh Hartnett in the movie, Eversmann received the Bronze Star Medal with Valor for his inspiring act of bravery and survival, which elevated him to hero status in the military and beyond. Eversmann later deployed to Iraq where he spent fifteen months during the Surge of 2007 and remained on active duty until 2008.

Eversmann has taught at Johns Hopkins University and the Army War College and authored the book

Walk in My Combat Boots with James Patterson. Eversmann currently works as a motivational speaker and, along with his wife Tori, founded Eversmann Advisory, which helps other veterans adjust to life after service. Matt and Tori are longtime summer residents in Sconset and frequent visitors to the island with their daughter.

Lets briefly talk about your high school and college experiences. Because when you look at your whole life’s work, you appear to have started on top and stayed on top. How did failure or disappointment motivate you early on?

I was born on Long Island but moved down south when my father got tired of taking the train into the city. I grew up in rural southwest Virginia. We had a little small farm in Natural Bridge, Virginia. I was the youngest of four: two engineers and a nurse above me. I went to school with no idea at all of what I wanted to do. Zero. I just assumed that I’d do some kind of business. I did OK in high school. Not great, but OK. I got into Hampden-Sydney College and promptly started my implosion academically from day one. Mercifully, by the end of my junior year, they asked me to take a break. I mean, it was like five semesters of academic probation. As I look back, I think that I just wasn’t mature enough. The best thing I probably could have done was join the Army the day after high school.

How did you gravitate toward the Army?

I was home on my little academic sabbatical. My father and mother had a small lumberyard and hardware store, and so I was schlepping Sheetrock all around Rockbridge County. One day, in walked a high school classmate of mine. He came in standing a little straighter, a little taller. Hair’s really put together. He told me, “I joined the Army … I’m stationed in Berlin.” I mean, that could have been Mars to me. He’s telling me these stories of watching these spy exchanges across the bridge. Going on missions on the Czechoslovakian border. To top it off, he was telling me they would go to Yugoslavia on leave [where there were] beautiful women and lots to drink. Anyway, that put the hook in. That night, I talked to my parents and said, “I think I’d like to go down and talk to the recruiter.” And they were very supportive and thought it was a very good idea.

What was your experience at the recruiter’s office?

I walked into the recruiting office and they had all these pictures of men and women soldiers in action. A tank and helicopters. There was this one picture on the wall. It was this very, very striking pose of an Army Ranger. It was an African American soldier. The perfect profile. His chin was like granite and perfectly shaved. At the time, the Rangers were the only ones that wore the black beret. Everything about this guy screamed perfection. I said, “That’s what I want to do.” The recruiters said, “First of all, that can’t be you … I think you should go into the finance core.” I said, “I failed out of school being an economics major. You don’t want me anywhere near anyone’s money.” I was able to convince him to let me enlist in the infantry. With that, off we went

How long before you were actually in the Army and saw active duty?

I wound up getting to my first assignment in 1988, up at Fort Drum, New York, in the 10th Mountain Division. But in 1992, I reenlisted with the opportunity to go to the Army’s 75th Ranger Regiment, in the special operations community. Because I thought, If I’m going to go to war, that’s the group I want to go with. So, in 1992, I get down there, and in August of ’93, we deploy to Mogadishu.

You were twenty-six at this point. Explain the assignment.

A humanitarian effort that winds up as a special mission to go capture or kill this warlord named Mohamed Farrah Aidid. This task force goes over, and I am a member of one of the teams that’s on the helicopter that’s going to provide security for the Delta Force guys as they go in on target.

Did you understand that there was genocide going on? That 300,000 Somalians were killed?

A little bit. Enough to know that this is pure evil. This is not a hard one to figure out. Honestly at the time, it was more the exclamation point of just having the opportunity to go to war … It’s easy to sound brave thirty years later. There’s this great excitement of getting to deploy, which is very real. But what is growing on me too, though, is now we’re literally going to get in-country.

We’ve done our wills, and we’ve done our powers of attorney, and there’s a big unknown, but I’m around a lot of guys that seem really brave and that’s kind of rubbing off. This is the real deal. Again, I’d never been deployed before, and there’s a lot of guys that had, but as it turns out, nothing like this.

You are given command. At that moment, was there any self-doubt?

We’re the last helicopter on this assault going in. All the helicopters are breaking their formation to the different points of insertion over this city block. We’re the last one going into all the dust and debris that has been stirred up and blown skyward. The pilot gets into basically a sandstorm and can’t see. So where we are stuck at the end, the clock’s ticking; you can just feel it, and the pilot’s like, “I can’t see anything.” Decision’s made. We’re going to go in here.

You thought it was going to be a grab-and-go—get Aidid out of there— but then what happens?

We have four problems right off the bat. We get inserted in the wrong spot. A kid falls out of the helicopter; he’s going to die if he doesn’t get evacuated. The communication with our radio, our lifeline, goes down. And then of course, we’re right in a firefight and this is all in like 20 seconds.

Human nature is fight or flight, and adrenaline either makes you want to run away or makes you run into it. What were you feeling?

I was stuck in some area between fight and flight. I know I had to do something. But I, myself, just me, I’m not sure what to do; I’ve got all these problems that I feel responsible for. You start to feel panic coming. This is all probably in seconds, but it feels like forever. And then something slaps you back. And for me, what slapped me back to the reality was watching all the soldiers, all the Rangers that were with me, just getting after it, getting right into the fight.

The situation devolved rapidly. Did you get overwhelmed?

There were a couple of moments when I thought, Man, this can’t get any worse. And then it would. I distinctly remember being in a vehicle thinking, “I’m going to get shot, I’m going to get killed and I can’t even fight back … Man, I hope it doesn’t hurt.” And then again, something else would happen. That was the scariest moment. The convoy I was in trying to get to the crash site eventually had to go back to the airfield because there’s still many wounded soldiers. There was no doubt that we wouldn’t just load up and go back.

Let’s fast forward to when the mission is over. You’ve come back; you’ve lost a lot of men. It has not gone even remotely the way everyone had hoped. What’s the feeling?

It is a mixed bag. One of our pilots had been captured by Aidid. So that really stings, of course. Then we saw the pictures of the Somalis dragging the bodies of the Americans through the streets, which was broadcasted all over the world. You just want to go swing the pipes. But then the decision comes out that we’re basically not going to do anything. The mission’s over. For all practical purposes, it’s over.

This decision came from the White House?

Yes, the president sends Ambassador [Robert] Oakley [as Special Envoy for Somalia] over. Oakley had a relationship with all these warlords and he got the word to Aidid: “Give them back—all the bodies—or were going to make October 3rd look like a picnic.” A couple weeks later, he agreed. That was it. POW Mike Durant was released on October 14th. A couple days later we picked up and left.

Were you feeling frustrated?

Horrible. Totally deflated. Like so many other guys, I’m going to go home and have to meet a twenty-three-year-old widow and explain to her what happened. She’s already been notified, so it’s not like I’m actually the one breaking the news. But I remember one of the psychologists saying, “Tell her as much as she wants to hear. Unvarnished. You feel like she’s getting enough, let her drive it. Tell her everything that she wants to know.”

Did you view this as a tactical failure?

No, just the opposite. This was a strategic failure but a tactical victory. When defining mission success, you learn that this whole idea of “without casualties” is Hollywood fodder. “I’m going to bring them all back alive.” That’s what we are trying to do, but that can’t be the criteria because there’s too many variables. So on that mission, we captured two of the blacklist bad guys and nineteen other Aidid cronies. We didn’t get Aidid, but the mission that day wasn’t Aidid. My realization was that war’s really ugly. It’s really, really ugly.

Did you feel like you performed well?

I think I did well enough. When I got back, I did a lot soul-searching [and] thinking. I realized there are some things I could have done better, could have done differently. Listen, if I’m going to go back to war, I’m going to go with this group. I really didn’t want to go back to school. That was the other thing. I think I’m decent at this. I think I’m good enough at this. I really do enjoy it. I like this Ranger business and I think it’s worth sticking around and trying to do it. Of course, you always look back thinking of all the things you did poorly, but there were a lot of things we did very well.

The events in Mogadishu impacted U.S. foreign policy for a long time. The United States has shied away from preventing genocides because of Somalia. What’s your reaction?

There’s a whole lot in that soup. As we got home, we had no idea what had been going on in Rwanda. None. Had no idea until we got home. I remember thinking, we’re this far away from them on the map. Why on earth would we not have gone to just stop this horror? The numbers that were broadcast in Rwanda made Mogadishu look like a Girl Scout camp and we did nothing. That’s when I realized I don’t want to be the world’s policeman, but there are just some things that I think morally we have the obligation. We’re the rudder of the moral ship. We, the United States, we do the heavy lifting. No matter what anybody says, we do. And we didn’t do anything there, and I thought that was beyond tragic. That was horrific.

You have since become a teacher of sorts. Is your new mission in life to disseminate what you have learned?

Broadly, it is. No one told me what it would be like on the battlefield. Even though there were people with combat experience that were members of that task force, no one ever said, “Hey, listen to me when I tell you, this is how you’re going to feel, this is how you’re going to react.” I’ve had to stumble through and figure a lot of this stuff out on my own. I thought that it sure would be a lot easier if you at least could give someone a little bit of a heads up.

Do you think heroism can be taught?

I don’t think so, but I think you can shape it. I think you can put men and women into situations where they have to do things that they’re very uncomfortable doing. Jumping out of an airplane. For some people, swimming. There are some things you can do to shape that mindset, but ultimately, I think heroism becomes a combination of several things. It’s a little bit of the surroundings, it’s a little bit of the mission, a little bit of that moral compass—and that all on any given day blows up in a moment.

How does the human instinct for survival enable someone to perform seeming superhuman feats, like flipping a car over that has someone trapped inside?

After going to Mogadishu, I totally understand how a mother lifts the car off the baby. Not only why she does it, but how she does it. She doesn’t know that she can. When you watch kids running into the fire and dragging somebody out without any regard at all, they don’t even realize they’re doing it. They just do it—and doing it for people they don’t even know personally. I do know that every single one of us has that fight or flight mechanism and on any given moment it could go the other way.New Paragraph

Can you really teach someone how to lead who’s not a leader?

No. Again, it’s another summation of a lot of theories and a lot of thoughts, but most importantly, you have to practice leadership. You have to physically do it. There’s been a lot of books written, but no one’s been able to write the definitive book about leadership because every person is different. We can generalize some ideas, and there’s some great rules to follow, but you learn by going out and doing it.

You’ve had a taste of the academic world, but your success has been in knowing, understanding and managing people. Is skill with people the ultimate skill in managing anything in life?

I think it is. It is probably the most important skill. I think that all the problems that we see both in the military and civilian/professional life start and end with leadership.

Today, no one wins, no one loses; you just participate. The victim is the criminal. You achieve too much success, you’re vilified. Everything is upside down. Does this create a disturbing future for leadership in America?

It does. I think we’re all fearful of that for a variety of reasons, whether we’re looking at political reasons or we’re looking at financial reasons that are going to affect us. We don’t have strong values-based leadership. How do we get out of it? We’ve got to showcase this exceptional talent for what it is. I think at the end of the day capitalism will win. Capitalism has to. Because all these kids can’t afford a lifestyle. Rich, poor, Black, white, Asian, Hispanic, doesn’t matter. You’ve got to get out and you’ve got to work.

Let’s talk about a big picture of the United States. We have always been the shining light of democracy. Our political system has always been what everyone has wanted to emulate, but there are cracks now that we have not seen since the Civil War. Where is America in the world’s eyes and where do you think this is going?

I haven’t been out of the country since 2018 or 2019. All you’ve got to do is spend five seconds in the Middle East to realize this is a great spot regardless of who’s in charge. Where we are now didn’t happen overnight. We’re in what I have called the “intellectual Sahara” for some time. And the events over the last 24-36 months have highlighted just how intellectually stagnant we’ve become for a variety of reasons. Whether we look at family, we look at the state of education, we look at the state of politics, we look at all of these things that affect us that have just been going on. Everyone’s been making the donuts for so long and all of a sudden here we are. And people are not thinking. The fact that we can’t have a polite disagreement about any political issue is absurd. First of all, there’s no civility because we’re too stupid to think about that. No one’s taught us to mind our Ps and Qs, follow the golden rule with your neighbor and sometimes “the less said, soonest mended.” But we’ve allowed this and it gets amplified through our social media. There’s the echo chamber stuff. You’ve got to shut that off.

You have put your country ahead of yourself. Do you feel an obligation to run for office?

No. I couldn’t imagine in this day and age putting my family through that again, a result of the old hitting yourself in the hand with a hammer. What I would like to do and I always keep my eye open is to maybe help somebody else out that’s running for office. I think that would be really exciting, to be on someone’s staff or behind the scenes.

And if you were to create in your mind a president that we need to put us back on the right path, what type of person would this be?

I think we must have a very moderate, professional, fiscally conservative kind of libertarian. I’m not a libertarian, but someone that thinks, “OK, let’s literally and physically bring our country back to the middle.” I think this person has to be exceptionally professional. They’ve got to be very likable, got to be a model; we need a poster child of the middle, that’s what we need. And listen, I’m a pretty conservative guy in general, I just am; I hope my blinders stay open. But I realize we understand there’s not going to be the perfect candidate, but common sense tells me it’s got to be a very moderate person that is willing to get us back on track. Strict constitutionalist. Our spending is out of control so we’ve got to reel it in. And we’ve got to know where we stand globally.

Do you think we should be getting more involved in Ukraine?

Old Matt was ready to go to war. The Russians have always been on the bad side of that equation. Less so it seems over the last decade, but all of a sudden here they are. So that all having been said, my hesitation to jump right in and say, “Hey, we ought to go and just stack skulls over there” is that I think I’ve learned a couple things between Mogadishu and fifteen months in Iraq. The first thing is what Colin Powell said in Mogadishu: “You break it, you bought it.” If you go in there and you break it and you think that Jeffersonian democracy is going to spill out, you’re wrong. The second thing is that the last time we threw a lot of dough in a proxy fight against the Russians was in Afghanistan as best I can remember. So if we’re going to stop Russia, let’s stop them. Let’s stop them in Ukraine. We sat on the sidelines of genocide before. Are we going to sit on the sidelines here? I think we either go in or leave.

Warren Buffett says no one ever made money by betting against the United States. We’ve always managed to pull ourselves out of any kind of tailspin. Are you an optimist about the United States?

I am. Absolutely. I think there is a large cadre of Americans on both sides of the aisle, of all shapes and sizes, that just want to get back to this American dream. I really believe that. And I think that where the pendulum shifts, it comes back to the middle. We just need some order so we can just all take a break. I also believe that when Americans start going overseas, they’ll realize that this is a pretty great place no matter who’s running this show. That’s the story and that’s what I’m sticking to.